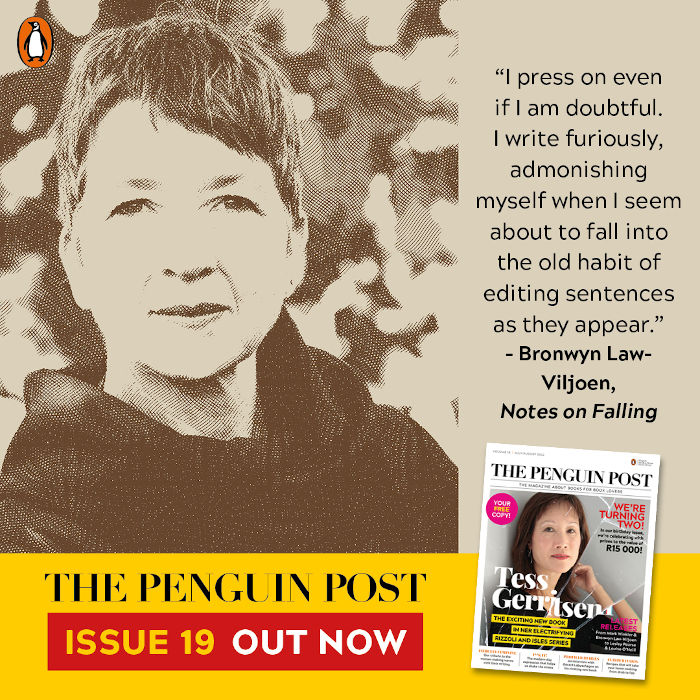

The First Text – Bronwyn Law-Viljoen on her new novel Notes on Falling

More about the book!

Early text works its way into the heart of the writer, but not necessarily the heart of the book, writes Bronwyn Law-Viljoen on starting a new project.

‘I press on even if I am doubtful. I write furiously, admonishing myself when I seem about to fall into the old habit of editing sentences as they appear.’

At the start of a new fiction project, there is always a piece written quickly, assuredly, with little hesitation, and with the euphoric feeling that comes with knowing one has found somewhere to begin. Since I am a slow writer and a compulsive editor, I try not to stop too often. I press on even if I am doubtful. I write furiously, admonishing myself when I seem about to fall into the old habit of editing sentences as they appear. I want to discover what it is I am going to be writing about, who is in the story and what they are doing there.

Usually, it is a character who drives this text, the first person of a new story. I am following her, tracing the contours of her mind, beginning to have a sense of what she looks like, though I don’t divulge this just yet. I am allowing this new character to do something, because it’s in the doing that personality is revealed. Is she running, perhaps, and if so, where to and how fast? Is this flight or exercise? Is she driven by a competitive streak, a need to run faster than the last time? Or does she not take note of how fast she is going? Because she doesn’t care, she’s not competing with anyone, least of all herself. When she runs, does she fix her attention on objects, buildings, the urban furniture she passes? Or is she inward-looking? Is there something that occupies her thoughts, so that she fails to notice how cold it is?

She’s remembering something, someone, an argument. She’s nursing a feeling of resentment, or regret. She has an old injury perhaps, a niggling pain in her ankle, or her knee. It’s not serious enough to stop her, but it does make her cautious of the terrain, the dips and divots in the path she is running. The path is in a city, it is late afternoon. No, later, early evening so that rush-hour traffic stops her at the streets she has to cross to get where she is going.

And where is she going? Is this simply there and back, a distance she has mapped out in her mind and run several times? Or is there a point, a landmark that she aims for? She’s run towards this point every day for the last few weeks and so it has become a goal. But there’s something else. She knows about this landmark, it’s important. It’s lodged alongside a memory of someone. It produces longing. Or maybe anger at something not said, or something said and regretted. No, her interest in this thing – this building, this bridge, this bench – is not emotional but intellectual. She’s curious. She knows of a famous person who lived there or crossed there or sat there. So, she runs towards it every evening partly because she’s trying to stay fit, but also because she’s compelled to go there for reasons both ordinary and, dare I say it, symbolic.

There are two possible fates for this first piece, this urtext. The first – the outcome most hoped for – is that it is lodged firmly in the story. It is an anchoring text, a piece of writing that initiates the world of the novel and the characters who enliven it. It is integrated seamlessly into a chapter or section, and it determines some of the most important stylistic choices about the project.

The second fate is that it is reluctantly abandoned, sometimes after years in which it is returned to, tinkered with, edited, honed, amended, polished. It has been mistaken for an urtext. Or perhaps it is that, but just not one that should remain. It has indeed been foundational, but the writing that comes after it is different in tone and style, and no amount of smoothing over and reworking can make it behave the way other parts of the novel do. And so, at the eleventh hour – and with the help of a sharp-eyed and dispassionate editor who has no sentimental attachment to this beloved and infuriating piece of writing – it must be jettisoned so that the story can, finally, float free.

Notes on Falling is out now.

This article was originally published in The Penguin Post, a magazine from Penguin Random House South Africa.

About the book

Thalia, adrift in a small university town in South Africa in the nineties, heads to New York to study photography and to pick up the faint trail left for her by someone she has never known. The city helps her to find her way as an artist, but it never quite provides the answers she is seeking. Only years later in Johannesburg is she able to make sense of who she is and what her work might mean.

Robert is a photographer in New York in the 1970s, desperate to make memorable images in a time of spectacular experimentation in dance, music and theatre. He intuits the importance of what he is photographing, but finds it almost impossible to transcend the troubles of his own life and achieve something great through his work.

Paige leaves South Africa in the seventies to pursue her dream of being a ballet dancer. She does not anticipate the ways in which this pursuit will challenge her understanding of the art that she has known and practised all her life, and she is ill prepared for the catastrophic moment that will undo everything she has worked for.

Unbeknownst to them, Thalia, Robert and Paige share a story that links them to one another, to the turbulent worlds of New York in the 1970s and South Africa in the 1990s and, finally, to the photographs that hold the secrets of their lives.

Notes on Falling is about the hope that art will challenge perceptions and orthodoxy so that the world can be reinvented through new forms. It is also about trying to reconcile the large pictures of history with the small snapshots of our individual lives.

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Bronwyn Law-Viljoen Notes on Falling Penguin Random House SA The Penguin Post