‘The struggle for free education matters’ – Read Malaika wa Azania’s Foreword to We Are No Longer at Ease: The Struggle for #FeesMustFall

More about the book!

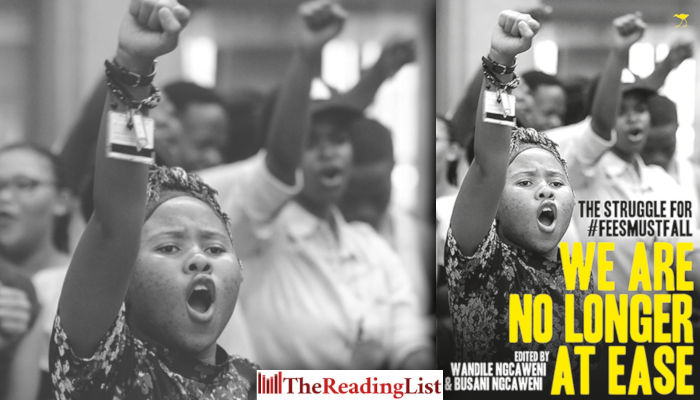

We Are No Longer at Ease is a collection of personal articles, essays, speeches and poetry mainly from voices of young people who were part of the student-led protest movement known as #FeesMustFall.

The book tells the journey of a youth that participated in a movement that redefined politics in post-apartheid South Africa, and is the evidence of a ‘born free’ generation telling their own story and leading discourse as well as action in transforming South Africa.

Read an excerpt:

~~~

Foreword

‘We revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe.’

– Frantz Fanon

The past five years have shaped the South African sociopolitical milieu in ways that are yet to be fully articulated and documented. Not since the apartheid dispensation has the country experienced rapture the magnitude of what it has in the last five years. After what seems like years of resting under the shade of the new democracy, young people of our beloved country decided that they could no longer stay in one place. Somewhere beyond the edges of the tree’s shade was a world at war. There was a civilisation that needed to be fashioned. A different South Africa, one that fulfilled the promise of a better life for all, needed to be born. After years of waiting on this new country, the youth realised it was not coming – that they were the ones they had been waiting for. They needed to stand up and step out of the shade, for in their bones they could feel that they were no longer at ease.

It is not an accident of history that young people were at the forefront of the recent struggles. Indeed, the youth has always been instrumental in the struggle for justice, not only in South Africa but throughout the world. In contemporary Africa, the young have made the terrain of struggle their dance floor.

The Y’en a Marre, a Senegalese youth movement, mobilised the youth vote to help oust President Abdoulaye Wade, whose administration had presided over worsening levels of poverty and inequality in the West African nation. The movement continues to be a thorn in the government of Wade’s successor, Macky Sall, with it continuously making demands for better reforms. The cascading uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa/Maghreb region (commonly and also problematically referred to as the Arab Spring uprisings) were predominantly led by the youth. The catalyst for these uprisings was the death of Tarek el-Tayeb Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor who set himself on fire in December 2010. His self-immolation was, at its heart, a demonstration against state sanctioned terror that characterises repressive regimes. Bouazizi was only 26 years old.

The Affirmative Repositioning Movement (ARM) in Namibia, led by young student activist Job Shipululo Amupanda, forced the government into redistributing land to poor working-class youth, who had been systematically thrust at the periphery of economic activity. Amupanda, former secretary for information, publicity and mobilisation of the SWAPO Youth League, was suspended from SWAPO for leading a land occupation campaign in 2014. A year later, a powerful movement that would create a seismic shift in South Africa was born. #RhodesMustFall, the foundation on which the #FeesMustFall movement was built, was born in the corridors of historically white institutions of higher learning.

The movement was a tool of resistance against pervasive institutional racism that defines higher education and, I daresay, the very fibre of South African society. In Memoirs of a Born Free: Reflections on the Rainbow Nation, I journey into the lived experiences of many a black working-class child who has to navigate the new South Africa that in some ways is not so new. Though statistics that paint the painful picture of structural inequalities in our country are released annually, they don’t sufficiently paint the picture of what racism in all its manifestations does to South Africans. They don’t articulate the extent to which it erodes the dignity that should be an inherent right. It is a violent and savage path to which no one should be condemned. Yet, for decades, it has been the experience of many poor working-class students, predominantly black, who have had to fight hard to open the doors of learning and simultaneously rethink and dismantle the legacy of imperialism that is characterised by unjust global hierarchies of knowledge production.

The #RhodesMustFall movement, though often derided by those who deem its cause capricious, was more than just a struggle about desecrating colonial statues and monuments of colonialism. It was an intellectual struggle that was seeking justice for the epistemological onslaught that African intellectuals and intellectuals in the Global South have been subjected to by the academy that is deeply resistant to change. It situated institutional racism in the broader struggle for transformation and above all, for justice. #FeesMustFall was not different in both substance and form. The struggle for free education has never been simply economic. Since the days of colonial resistance, free education has always meant education that is free to access and that is freed from imperial logic.

On a number of occasions, I have heard some political analysts and commentators refer to the #FeesMustFall protests as spontaneous, implying that they occurred as a result of a sudden impulse, that they were without any stimulus. This characterisation is deeply problematic. It fails to trace the barometer of struggle that led to that historic moment that has, in many ways, shaped the discourse around the depths of the crisis in higher education in South Africa. This struggle cannot be articulated outside a deep understanding of the history of our country, for it is in the womb of imperialism, colonialism and apartheid that the contemporary crisis of higher education gestated.

To paraphrase Elliot-Cooper, geography was a vital component in shaping the imperial ambitions of nation states, but it is also true that imperialism affected more than just the spatiality of colonised nations. It interrupted and, in many ways, annihilated the very ways of life of the colonised people. Godlweska and Smith in their 1994 book Geography and Empire contend that this created permanent links between spaces and places that are divided by physicality, but yet are interconnected through ideology and appropriation – the ideology of capitalism that underpins colonialism and apartheid. Even in the democratic dispensation that is seeking to fashion a different society, universities remain a postcolonial microcosm of this devastating legacy. And this is why #FeesMustFall matters.

But to romanticise the #FeesMustFall movement would be a cruel exercise in the rewriting of history; cruel because it would deny the legitimate pain that was suffered by many within the movement. While the movement was progressive in many ways, it also had deep-seated regressive elements that ultimately eroded its revolutionary character. The support-repelling tactics that the movement would later adopt, characterised by the burning of university buildings, the violence targeted at students who did not want to be part of the movement’s activities and the aggressive intolerance to dissent were just some of the counter-revolutionary elements that eventually annihilated the moral high-ground that was an important pillar of the movement.

But perhaps the greatest weakness of the movement was the resistance by some of its male leaders to recognise the importance of waging an intersectional struggle. This movement comprised an eclectic blend of people – both in terms of the activists within the movement and those on the outside lending their support – but was often not the safe space that it was supposed to be for women and for the LGBTIQA+ community that in reality was an integral force behind the strength and legitimacy of #FeesMustFall.

I distinctly, and painfully, remember a meeting of #FeesMustFall activists from across the country that was hosted at the Parktonian Hotel in Braamfontein, where the depth of the patriarchal violence within the movement was put on display. A number of male leaders, when confronted about the disregard for the feminist question, boldly spoke about how the struggle was about liberating black people first, and all else would follow. This violent masculinity became a big feature of the movement, attempting, though with constant resistance, to own the narrative of the struggle.

In spite of what became of the movement, it remains important. The struggle for free education matters. We cannot hope to fashion a higher civilisation without attaining this goal. In the words of Arundhati Roy: ‘Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. Maybe many of us won’t be here to greet her, but on a quiet day, if I listen very carefully, I can hear her breathing.’

Malaika wa Azania, author of Memoirs of a Born Free: Reflections on the Rainbow Nation and student at Rhodes University

Categories Non-fiction South Africa South African Current Affairs

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Busani Ngcaweni Jacana Media Malaika wa Azania Wandile Ngcaweni We Are No Longer at Ease