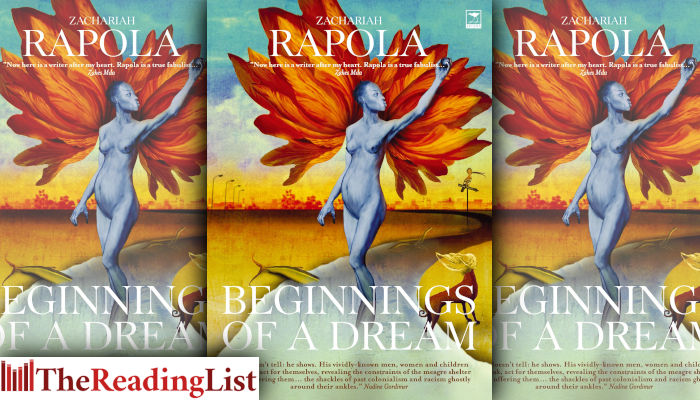

Read an excerpt from Zachariah Rapola’s award-winning short story collection Beginnings of a Dream

More about the book!

Jacana Media has shared an excerpt from Beginnings of a Dream by Zachariah Rapola.

Beginnings of a Dream won the 2008 Noma Award, a prize for outstanding African writers and scholars who published in Africa.

‘Now here is a writer after my heart. Zachariah Rapola first captivates me with his simple and lucid yet rhythmic diction. And then he seasons his stories with the ancient wisdom of proverbs and other idiomatic expressions. He portrays generational and cultural contradictions with empathy and humour. He paints for us a fabulous world where the supernatural and the strange exist comfortably in the same context as objective reality. These very modern stories are therefore a conversation between the living and the fourth dimension – the world of the dead and the unborn. Rapola is a true fabulist whose stories go beyond the documentary realism of most of South African fiction to a hyper-realistic plane of African orature.’ – Zakes Mda

About the book

Plunging the reader into a phantasmagoric world where streets are paved with human remains and men are apocalyptically condemned to death by the fire of their loins, these short stories strike a fabulist and magical realism drawn from African traditions and present-day conditions.

For all its contemporary relevance, this collection has at its core a dialogue between the living and their ancestors that creates a powerful resonance between the bones of the dead and the echoes of their survivors.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Beginnings of a Dream

Birth is the beginning of a dream

a meditative pose over knights and queens

on the tightrope,

a juggle of divining bones

striving to interpret man’s prodigal wanderings

through the Minotaur’s labyrinth …

Birth is the beginning of a dream … In my old age, I am able to muse. My grandchildren dismiss my observations as senile rattling – and how can I chastise them for their ignorance, when even my four adult children push aside my accumulated insights as ‘grandmother’s tales’? Perhaps they are right, how can I tell? Increasingly, my thoughts are becoming blurred by dust and drifting winds.

I overheard Thekiso, my sixteen-year-old grandson, whisper to Itumeleng, his ten-year-old sister: ‘Hai! Tsamaya, go keep grandmother company. Can’t you see she is desperate for an audience?’

Desperate for an audience! This is how the insights of my old age are viewed. Trivialised and trampled upon. Dismissed as bothersome.

Maybe Thekiso is right. I know I am constantly talking to them – when they are doing their homework; when they are trying to enjoy their favourite television and radio programmes. In regard to interrupting their homework, I too feel I might be intruding. But I cannot agree with them when it comes to the other things. For, in my long years, I have learnt a lot. I have accumulated knowledge and information, and discovered that these two instruments, radio and television, offer nothing good. The parables and wisdom that age has nurtured in my head are lacking in them, as are the revelations and inner resourcefulness that rains and winds have nourished in me. Increasingly, with the advance of age, I realise that these appliances are contraptions designed to curb the growth of inner knowledge.

Innocent grandchildren, how can I chastise them? Their innocence and ignorance is the mandatory price of youth.

It is Raisibe whom I cannot forgive. Raisibe, my first-born. I could have excused her were she a boy, for then there might have been a wife whom I could blame instead, since it is true that wives are experts at souring relations between mother and son. The worst was when she called me a witch. That was seven years ago. I wonder how that husband of hers copes?

Birth is the beginning of a dream … and a fragment of that epic dream exploded into a nightmare in 1980. That is when Madika died. At sixty-eight, I found myself a widow. Maybe because we had got so used to each other, the two of us had started believing in our immortality. Not that death didn’t visit us; it was just that we were too stubborn to host him. We were prepared to sink into the grave together, so that we might walk side by side in the hereafter. It is now almost twelve years since Madika’s death. And here I am, alone. Still, I am grateful for my luck. Few people can withstand the assaults of old age as I have. I have also given up counting the white hairs on my head. And you wonder whether I am grateful or not – of course I am. But here I am, all alone in this shadeless world. Occasionally, I venture outdoors. But a hostile world always sends me scuttling back into the familiar comfort of the house. My ears can no longer wander out to visit different sounds or voices. My eyes, too, no longer can sprint about, entering the sealed windows of other homes. Only my voice strolls around the house. Still, my children and grandchildren, like everyone around me, at times erect walls around their ears. ‘Oh grandmother, please …’ In my old age, when the word ‘please’ should be pleasing to hear, it is now like a needle that pierces the core of my heart. I blame Raisibe for that. Raisibe is the worst. On her occasional visits, she uses the standard: ‘Oh grandmother, please – you’ve had your breakfast / lunch / supper / snuff … what more do you want?’

As if I live only for food and snuff. As if I were not her mother. She surely treats me like her stepmother – one of those frowned-upon fleas that drain the blood bond between fathers and their children.

That is why I feel betrayed by Madika. His sneaking away to the beyond without taking me. Had death made his advances to me instead, I certainly would have informed Madika, and invited him to come along – even dragged him.

‘Hai! Tsamaya, go keep your grandmother company …’

Thekiso has changed a lot. He has changed for the worse. It must be that mother of his who is putting bad things into his head. I remember how attached the boy was to me. That was until he turned eleven. Then he discovered the bioscope. He stopped brewing grandmother’s favourite coffee; stopped boiling grandmother’s Maltabella porridge. He didn’t care any more to bring her warm milk after supper. I spent hours contemplating these disappointments, and concluded that old age was a curse.

Looking after my grandchildren is my greatest pride. Caressing their innocent little faces used to thrill me. Mother! Foundation rock of the family. Like the baobab tree, sustaining life throughout the centuries; stretching out her firm hands to protect her children, like the bark of the baobab protects its roots so they don’t get bruised when drawing water. And Madika is looking after our children and grandchildren from the beyond – the world of the ancestors.

I know I will join him. All the meandering footpaths in this world lead to death. One day I will escape from this lonely life … this bondage of old age.

~~~

Categories Fiction South Africa

Tags Beginnings of a Dream Book excerpts Book extracts Jacana Media Zachariah Rapola