A seminal boyhood moment played out against the backdrop of political upheaval – Read an excerpt from Tony Peake’s North Facing

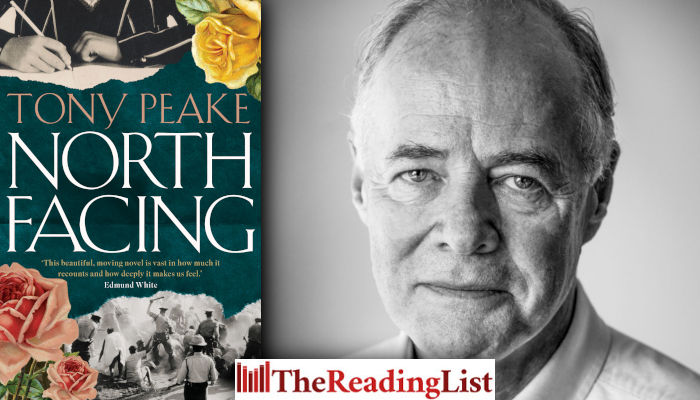

Jonathan Ball Publishers has shared an excerpt from North Facing by Tony Peake.

About the book

Peake’s first novel for 20 years is an exquisitely realised story of revisiting a seminal boyhood moment as it plays out – with unexpected and sinister consequences – against the backdrop of political upheaval in South Africa.

For one long, intense week in October, 1962, it looked like the world might end as the Cuban Missile Crisis brought with it an East-West stand-off and the possibility of nuclear holocaust. This dark, bittersweet novel evokes the unease of the period through the experience of a young boy in Pretoria caught up in South Africa’s political unrest following the Sharpeville massacre, Nelson Mandela’s arrest and the State of Emergency.

When Paul Harvey, sensitive, isolated and desperate to fit in at school despite his English parents, is invited to join the most popular pupil’s gang, he will do whatever is required to please the ringleader Andre du Toit. Little does he realise that Du Toit is acting for his father and their friendship is a cover for finding out more about Paul’s parents and their friends.

A charismatic teacher tries to teach the boys about what is happening in the world around them – including racial inequality and the Cuban Missile Crisis – and they become suddenly aware of life beyond the school boundaries. The pupils sense hidden dangers looming, Paul’s parents hear of the house arrest of a left-wing friend, the far-right is in the ascendant and South Africa is no longer safe. Added to this sense of unease, the growing realisation of his sexuality and the part he has unwittingly played in the drama unfolding sets Paul still further apart from his peers.

Now a man in his 60s and living abroad, Paul is drawn back to Pretoria to revisit his boyhood home. It has taken him most of his life to grasp and make sense of his past: the other boys, the masters, his own and Du Toit’s parents who so puzzlingly populated and controlled his world.

About the author

Tony Peake was born in South Africa but has lived most of his life in London. He is an acclaimed short story writer with work in many anthologies including The Penguin Book of Contemporary South African Short Stories, The Mammoth Book of Gay Short Stories, and Best British Short Stories 2016. He is the author of two previous novels, A Summer Tide (1993) and Son to the Father (1995), and the authorised biography of Derek Jarman (1999). For the last 30 years he has been a literary agent.

Read an excerpt:

~~~

‘I don’t understand it,’ Paul’s mother was saying. ‘Mrs Merinkavitch manages and she hardly pays her garden any attention, just leaves it to her boy. Who, I might add, looks gormless.’

She was in her gardening clothes: a dun-coloured skirt long since demoted from best, a plain blouse, a pair of scuffed leather shoes with low heels, and, of course, owing to her mistrust of the sun, a wide-brimmed straw hat that obscured the fineness of her dark, wavy hair. In her gloved hand was a trowel.

‘Back home,’ she went on, ‘Granny always used to say what green fingers I had. This climate, though …’

Grasping Paul’s shoulder – for she’d been kneeling on a strip of sacking before the flowerbed in question – she used him to lever herself upright.

‘In England you crave the sun. All the best houses are south-facing. Lack of rain is never an issue. Well, hardly. Things grow. And grow and grow. Willy-nilly. But here … ’ She let the trowel in her gloved hand fall against her skirt, smearing it with dust.

Paul lived with his parents in a small village that was generally regarded as being a cut above other such settlements on the fringes of Pretoria. Quarter-acre plots, common elsewhere, were non-existent in posh Nellmapius. In Nellmapius an acre was about the smallest you could get, with the result that trees were abundant; and, since greenery was, on the highveld, to be desired, so too was the village. Charming, people said. So different from its neighbours, so – well, English, they supposed. The sort of place where a person with Peggy’s background might feel quite at home.

‘It really is hopeless!’ she concluded, gesturing with her trowel towards her wilting Transvaal daisies. ‘Why do I even bother?’

Paul, wanting as ever to be supportive, replied brightly, ‘But people always say how nice you’ve made the house. Everyone who visits, they all say that.’

It was an undistinguished building, the bungalow they inhabited; not at all desirable, or charming. Still, Paul was right. By dint of chintz and oak, Persian rugs, ornaments of a somewhat antique nature and pictures that often featured the English countryside, here Peggy had somehow contrived to hold her own. The house’s only African aspect, apart from its architecture – the metal windows, the red tin roof – was Mosa, their maid.

Every morning, she’d emerge from behind the garage, where she occupied a room that smelled powerfully of paraffin and had in it, unlike the fussily furnished house, the barest minimum: just a chair, some hooks on the wall for her clothes and a single bed kept on bricks in order, as she’d once explained to a wide-eyed Paul, to deter an evil spirit called the tokoloshe, who liked, among other things, not specified, to bite off a sleeping person’s toes. Your only defence against it was bricks because, being small, a tokoloshe couldn’t, praise the lord, climb a brick.

From these cramped, smelly and potentially life-threatening quarters, Mosa would take up her early-morning station in the kitchen to brew the day’s first pot of tea. This she would then carry, on a tray she’d laid the night before, to the master bedroom; although, now that Paul was boarding, during term-time, it was only on exeats that he still experienced the rhythms of life within the Harvey household.

On a Sunday, these were: his father, having collected Paul from school, would spend the morning in his workshop in the garage, while Peggy either tasked Mosa in the kitchen, or tended her hopeless garden. Then a substantial lunch at the oak table in the dining room, for even in high summer the Harveys never ate on the stoep, or braaied. Rather, they sat down at a formally laid table to a substantial roast, a medley of vegetables, a specially prepared pudding, all served by Mosa. Followed by a period of obligatory quiet, which Paul was required to spend in his room. Then tea in the lounge – which Peggy would serve herself, Mosa having by now been given ‘off’ – where Paul was made to eat so many sandwiches, always the sandwiches first, and so much cake – We can’t have you wasting away, dear! – that, by the time he clambered into the car to be driven back to St Luke’s by Douglas, the dread he habitually felt at having to leave the security of home for another week of school was intensified by indigestion to the point where his stomach would actually be aching. Sometimes he even thought he might throw up.

Though on the weekend after Du Toit’s extraordinary nocturnal invitation, life hadn’t, in fact, been following its usual patterns. In keeping with the strangeness, the surprise, the shock of that invitation, anomalies abounded, starting with Saturday’s game of cricket against KGPS; or King George Preparatory School, to give St Luke’s brother establishment its full name. Because the match was being played at home, after morning lessons and lunch those seniors not in the team had to present themselves on the sidelines in support of their first eleven. Also gathered there were some parents, the fathers in shorts and T-shirts mainly, the mothers in equally casual summer dresses, enticing dashes of colour against the field’s prevailing green. Barring one pale father, who stood out in a beige suit, and one pale mother, whose skirt reached down to her calves when every other dress on display was above the knee. Making Paul wish, as he ran towards his parents – the sight of them always caused him to break into a run – that they could have been different. Or rather, not quite so different. That was what he really wanted. For them to blend in.

‘Hello, darling. My, you look hot!’ said Peggy, planting her customary kiss on his sweaty forehead, something else he could have done without. ‘Must you always run so, instead of walking?’

Douglas, thankfully, was less demonstrative. He only lifted a vague hand, being anyway in conversation with Spier.

‘How was Monday’s test?’ continued Peggy. ‘Had you done enough revision? I wasn’t sure from last Sunday. And your tuck? Did I bake sufficient?’

Here a heavy hand laid unexpected claim to Paul’s shoulder and he heard a deep voice saying, in a rumbling Afrikaans accent, ‘You’re Paul, right? I recognise you from Andre’s description. Don’t act surprised. He’s told me all about you. Oh, yes.’

Paul looked up into a pair of cat-like eyes, greenly set in a sunburnt face.

‘And what I’m wondering is: would you like to come out with Andre on tomorrow’s exeat? Back to our place, I mean?’

Douglas and Spier had both fallen silent.

‘I’m sorry, but I don’t think I … ’ It was Peggy who broke the silence.

‘Koos,’ said the man, extending a beefy arm. ‘Koos du Toit.’ He turned to shake hands with Douglas too, nodding briefly, as he did so, at Spier. ‘Afternoon, Spier,’ he said, then cleared his throat. ‘I don’t mean to put your boy on the spot or anything, but he and my son are such good friends, or so Andre’s been telling me, Mrs … Harvey, isn’t it?’

‘Please,’ said Paul’s mother, ‘call me Peggy.’

‘And I’m Douglas,’ said Paul’s father.

‘Me you know,’ said Spier.

‘Ag, we all know you, Mr Spier,’ said Du Toit’s father with a barked laugh. ‘You pop up all over the place.’ His eyes, however, stayed on Peggy. ‘So – how about it?’

First Du Toit at my bedside, Paul was thinking, now this! What could it all mean?

Peggy sounded taken aback too. ‘That’s very kind of you,’ she was saying, a look Paul couldn’t recall having seen before entering her usually judicious grey-green eyes, ‘but I’m afraid that tomorrow we have plans.’

‘We do?’

Peggy shot her husband a more familiar look. ‘Honestly, Douglas! You must remember! Father Ashley – yes? – and Simon. Simon’s coming too. I’ve shopped and everything.’

‘Simon?’ interjected Spier. ‘You don’t by any chance mean Simon Tindall, do you?’

‘Why?’ said Peggy. ‘Do you know him?’

‘A bit.’

‘Like I say,’ said Mr Du Toit, ‘our Mr Spier pops up everywhere. But, for those of us who haven’t got a finger in every pie, you have to tell me, Peggy, please! Who are these blerrie people?’

~~~

Categories Fiction International South Africa

Tags Book excerpts Book extracts Jonathan Ball Publishers North Facing Tony Peake