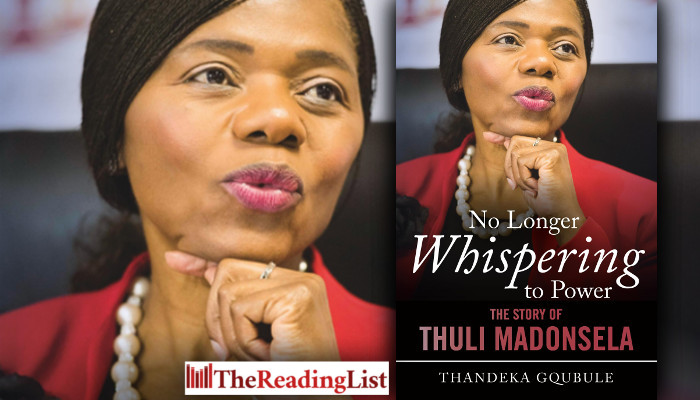

Jonathan Ball Publishers has shared an excerpt from No Longer Whispering to Power: The Story of Thuli Madonsela by Thandeka Gqubule.

Gqubule has practised as a journalist and worked in the media for nearly three decades. She has followed the story of former Public Protector Thuli Madonsela with great dedication and passion.

The excerpt comes from Chapter 9 of the book, in which Gqubule examines Madonsela’s less-famous reports, which were vital steps towards a better South Africa.

~~~~~

Chapter 9, ‘Dignity, the neocolonial state and the party: Thuli Madonsela’s other reports’

Thuli Madonsela may be renowned for her groundbreaking reports on the Nkandla and state capture scandals, but these were a mere two among many. It is in the thousands of her other reports that her values continue to shine through, and we realise the depth of her commitment to social justice and her engagement with a range of themes so crucial to South African society today: a jurisprudence of dignity, the neocolonial state, Big Man syndrome, and the conflation of the state and the party.

So, let us meet Michael Komape – or, at least, hear his story.

The hope of his impoverished family, Michael was a lively and happy six-year-old in his first few days in Grade R at Mahlodumela Lower Primary School in Chebeng village, outside Polokwane. It was in Polokwane that President Jacob Zuma first received his mandate to govern, on the back of his promise to the ANC and the people of South Africa that he would enact pro-poor policies.

The South African Constitution guarantees dignity to people like Michael. Dignity is the supreme value underlying the last two centuries of universal moral, political and philosophical thought, the concept that underpins most traditions of jurisprudence.

Michael, of course, knew nothing about dignity or jurisprudence. He just knew, one Monday morning in January 2014, that he needed to go to the toilet. He turned to a six-year-old classmate, informing his buddy that he needed to go. The two went off during a break between classes.

The toilet that the two little boys considered normal was a pit latrine, filled with faeces. A pit latrine is a large pit dug out below a toilet seat. The pit latrine at Michael’s school was deep – likely several times deeper than Michael was tall.

It is thought that the toilet seat collapsed, sending Michael hurtling into the pit. He must have struggled for his young life before surrendering, defeated, to the abyss. His friend went back to class, perplexed and concerned about why Michael had not come out of the toilet yet. Hours later, when he was asked, he told the teachers, who were searching frantically for him, that he hadn’t seen his friend since they had gone to the toilet that morning.

Members of the community joined in to help retrieve his lifeless body, which was hauled up to the ground as evening approached. The police arrived. An inquest docket was opened.

The indignity of Michael’s death shocked his mother. Children are buried in white coffins, here, in Michael’s country. But, no matter how clean his pale wooden coffin looked, nothing could quell the stench of scandal emanating from how he had died, 20 years into South Africa’s democracy.

There were no modern toilets at Michael’s school. According to a report by the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) – compiled under the watch of Thuli Madonsela’s predecessor in the Office of the Public Protector, Lawrence Mushwana, and presented to Parliament in 2012 – 1.4 million households used pit latrines at that time; put differently, 11 per cent of South Africa’s population had no access to dignified, modern toilet facilities in 2012.1

In a country whose Constitution is said to have the most significant and sweeping jurisprudence of dignity, Michael’s life was cheap – and real dignity remains a pipe dream, as politicians squander money meant for the poor.

In Madonsela’s 2013 report Pipes to Nowhere, she estimates that the government will need R44.5 billion to resolve the country’s sanitation crisis. The SAHRC concurs. The report also explores the issue of dignity as a right. It is steeped in an understanding of the social and economic relevance of dignity. In it, Madonsela communicates the message that dignity is not only the primary right that underpins the South African Constitution, but also the obligation of every citizen: each of us is duty-bound to uphold the right of others to dignity. Madonsela has lived this notion by demonstrating it in the way she has treated even those found to be on the wrong side of her rulings. Every human being has the responsibility to treat every other human being in a dignified and humane way.

In this regard, the Declaration of Human Duties and Responsibilities (DHDR) is instructive. Compiled in 1998 to celebrate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights’ 50th anniversary, the DHDR holds that every person – regardless of gender, ethnic origin, social status, political opinion, language, age, nationality, or religion – has a responsibility to treat all other people in a humane way. It has parallels with the African philosophy of ubuntu, which Madonsela extolled during her tenure as Public Prosecutor. Ubuntu is the belief in the essential human virtues of compassion, humility and humanity, the belief that we should always choose understanding over vengeance. Scholar Michael Onyebuchi Eze summarises the essence of ubuntu as follows: ‘“A person is a person through other people” strikes an affirmation of one’s humanity through recognition of an “other” in his or her uniqueness and difference. It is a demand for a creative inter-subjective formation in which the “other” becomes a mirror for my subjectivity.’ How can one be whole and at peace, then, while Michael Komape’s life is one of indignity and suffering? Eze continues:

This idealism suggests to us that humanity is not embedded in my person solely as an individual; my humanity is co-substantively bestowed upon the other and me. Humanity is a quality we owe to each other. We create each other and need to sustain this otherness creation. And if we belong to each other, we participate in our creations: we are because you are, and since you are, definitely I am. The ‘I am’ is not a rigid subject, but dynamic self-constitution dependent on this otherness creation of relation and distance.

If there was no deficit of ubuntu in South African society, Michael would still be alive today, playing soccer in the dusty playground. He would be happy and well.

According to Madonsela, those entrusted with social and political power hold their power not for themselves, but to facilitate the progress of society. Human civilisation moves forwards through acts of humanity; contributions to the arts, humanities, sciences, law and institutions; and the material giving and sharing of resources. So, she believes that, when public resources are misappropriated, the relief that this money was designed to bring is diverted to serve public consumption instead of the public good. This kind of misappropriation is unlawful. It leads to deficits in both integrity and ubuntu in society.

Most importantly, it leads to the death of children like Michael.