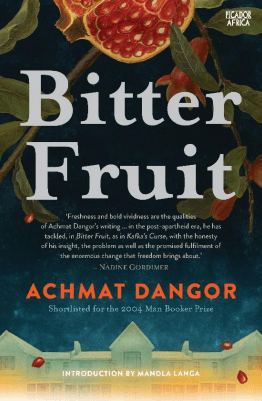

A new edition of Achmat Dangor’s acclaimed novel Bitter Fruit is out soon from Picador Africa, ahead of the publication of his new novel, Dikeledi, in August.

The new edition features a wonderful new introduction by Mandla Langa, and a stunning new cover.

First published in 2001, Bitter Fruit was shortlisted for the IMPAC Dublin Award and the Booker Prize.

The novel tells the story of a Coloured family in around the time of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and a history of Umkhonto we Sizwe and the apartheid security police that come back to haunt them.

Read an excerpt, taken from Chapter 5 of the novel:

NO, SILAS AND Kate had never ‘jolled’, which was a township way of describing an affair, though many people were firm in the belief that they must at least have slept with each other, just once, as an experiment. After all, he was a black man and she was a white woman, and when they had been active in the movement, breaking the racial barrier was like breaking the land-speed record or shooting an AK-47 for the first time. It created the same fleeting excitement, sleeping with someone of another colour.

Alec had once told Silas he found it incredible that he had never tasted a ‘nice piece of silverside’, and that Kate being a ‘double adapter’ must have made it all the more exciting. Silas’s angry response had only reinforced Alec’s suspicion that he was being devious and unnecessarily coy. ‘Shit, everyone knows that white cherries want black ouens because white ouens don’t know how to naai.’

The fact was that Kate and Silas had reasons greater than their own morality for not having sex with each other. They had been in the same MK counter-intelligence unit, and their job was to identify infiltrators and informers, a very difficult task, if they wanted to be objective and retain their integrity. There was no room for clouded judgement; it could allow an enemy in your midst to go undetected or condemn an innocent person to being cast out like a leper.

Once suspicions had been aroused about someone’s reliability, it was difficult to redeem them. The enemy went around spreading rumours about comrades, planting suspicion about the best of MK’s soldiers, hoping to sow disarray in the ranks of the underground army. Counter-intelligence’s biggest challenge lay not in the unmasking of traitors but in proving the innocence of those who had been falsely accused. Good and loyal comrades were subjected to isolation and scorn, unspoken

but obvious. They could end up being assassinated by some overzealous and misinformed MK infiltrator from abroad, alongside the askaris – MK soldiers who had been captured and ‘turned’ – or impimpis who sold their comrades for money, or even those who had been broken by the security police and could not help being traitors.

Being in counter-intelligence gave you a certain amount of power, and it was tempting to use this power to get rid of rivals, real or imagined. Generally speaking, having affairs inside MK was bad enough, fucking with someone in your own intelligence unit was fatal. Infidelity among comrades, jealousy, the suspicion that your wife or husband or lover was sleeping with someone else in MK, often achieved what the state could not: it turned a loyal soldier into a traitor. In their quiet, intimate moments, Silas and Kate often whispered about a notorious case where one of their bravest operatives, a close friend, secretly started working for the cops because he had discovered that his wife was jolling with her unit commander. The cops trapped the errant lovers and shot them both, while the traitor himself was ‘fed’ to MK and killed as a consequence. A lot of good people dead, a whole network smashed, ‘All for a fuck!’ people would say.

Kate and Silas always stopped short of such summary condemnation, as both remembered how close Silas had come to being ‘compromised’ because of an indiscretion, a moment of weakness (‘Don’t make it sound so Christian!’ a scornful Lydia would tell him). He had had an affair with another MK comrade, a courier, not in their unit, but it was still dangerous. And most of all, his timing was wrong.

One day, must have been about December 1988, Lydia would say if you asked her, Kate had turned up at the clinic where Lydia worked, and asked to speak to her alone, somewhere private. They went out into the garden, and sitting down next to Lydia, on a bench under a tree, Kate leaned close, like an old friend, only to reveal that she and Silas were members of the ANC underground and that he had a problem.

‘What kind of problem?’ Lydia demanded.

Kate looked around, as if to say, ‘This is not a game, not just idle gossip I’m bringing you, it is a matter of life and death.’ Silas had been ‘indiscreet’. He had had an affair with a comrade, a woman who did sensitive work for MK. They now had to prevail on this woman to leave the country, without her two young children. They were afraid that she was susceptible to pressure because of her children, and because her husband was a respected ‘up and coming’ lawyer who did lots of sensitive political work. The woman might break, reveal things.

‘Who are they?’ Lydia asked.

‘We,’ Kate answered coldly, lit a cigarette, and went on speaking as if lecturing an innocent child about the dangers of life. ‘We think the cops know of the affair and may try to exploit it, use it against us.’

‘So they know that Silas is in the underground, as you call it?’

‘Yes. Among other things.’

Lydia realised that Kate was testing her, wanting to see how much she knew, whether Silas was a talker, someone who confided in people close to him. She said: ‘Then why don’t they simply arrest both Silas and this woman? That’s what they usually do.’

‘Because Silas is untouchable, at the moment. Involved in something so important that they dare not arrest him. They would prefer to compromise him.’

Lydia shook her head in disbelief, the bewilderment of suddenly finding out that her life, her son’s life, that of her mother and father, her whole family, was fragile, subject to someone’s whim, their freedom dependent on how much people thought they knew or did not know.

She did not pursue the many questions that arose in her mind: How long has Silas been in the underground? How long has he been sleeping with this woman? Who is she? She did not like Kate, and saw no point in having a long conversation with someone who was unlikely to see the world from any perspective but her own. She also resented her, not because she was jealous of her, not in any physical sense – indeed, she saw in Kate a ruthlessness, manlike and brutal, that would have prevented a sexual relationship with Silas. No, Lydia resented this woman, this white woman with her nicotine-stained fingers and wiry looks, because she shared secrets with her husband, because she had the kind of relationship with him that she herself had never been able to develop. Imagine people sharing the intimacy of deadly knowledge, confiding in each other, in secret places, at designated times. They may as well also fuck each other.

But above all, what incensed Lydia was Kate’s simplistic righteousness, her clear definition of right and wrong, not so much of who was a comrade and who an enemy, but of who was useful and who was not. Her unspoken assertion that this distinction justified any kind of behaviour added insult to the hurt of Silas’s ‘indiscretion’. What mattered to Kate was how the problem was resolved, the need to protect the ‘movement’ at all costs. The morality of Silas’s actions and their effect on Lydia were immaterial.

‘I have to get back to my work,’ Lydia said, and got up. Kate laid her hand on Lydia’s shoulder, then abruptly withdrew it.

‘Listen, Lydia, in six months, a year from now, none of this will matter, people will no longer be hunted down, there will be no need for an underground. Silas is too deeply involved in that process to be pulled out now. Help him stay there, please.’

It was not a plea but an order, as if she had rehearsed the words and, like any good actor, was improvising their sequence, trying to produce the maximum effect on her audience.

Gradually, Silas began to talk about the ‘incident’, more as a way of justifying what he had done, Lydia thought, than out of any real sense of remorse. The fact that his lover, whose identity was still a secret, had been sacrificed and sent into exile, weighed heavily on him. It also threatened his career. She would return, reunite with her husband, or divorce. Silas’s selfishness, and the underground’s cruelty in separating her from her children, would be revealed. After ‘1990’, when ‘the war’ had ended and ‘comrades’ were able to associate with each other openly, Lydia heard Silas’s MK colleagues casually boast how difficult life in the camps had been, as if gratified by their own suffering. She imagined what it must have been like to be sent out in disgrace, as it were, for having been indiscreet, for having slept with someone in a senior position, how it must have created the image of a shamed woman, a soldier ‘fuckable’ for the cause. How much leering this nameless woman must have endured.