‘Be quiet and be calm, my countrymen, for what is taking place is exactly what you came to do … Brothers, we are drilling the death drill .’ – Reverend Isaac Wauchope Dyobha

Paris, 1958. A skirmish in a world-famous restaurant leaves two men dead and the restaurant staff baffled. Why did the head waiter, a man who’s been living in France for many years, lunge at his patrons with a knife?

As the man awaits trial, a journalist hounds his long-time friend, hoping to expose the true story behind this unprecedented act of violence.

Gradually, the extraordinary story of Pitso Motaung, a young South African who volunteered to serve with the Allies in the First World War, emerges. Through a tragic twist of fate, Pitso found himself on board the SS Mendi, a ship that sank off the Isle of Wight in February 1917. More than six hundred of his countrymen, mostly black soldiers, lost their lives in a catastrophe that official history largely forgot. One particularly cruel moment from that day will remain etched in Pitso’s mind, resurfacing decades later to devastating effect.

Dancing the Death Drill recounts the life of Pitso Motaung. It is a personal and political tale that spans continents and generations, moving from the battlefields of the Boer War to the front lines in France and beyond. With a captivating blend of pathos and humour, Fred Khumalo brings to life a historical event, honouring both those who perished in the disaster and those who survived.

Read an excerpt:

‘Pitso,’ started Tlali as they were eating dinner one evening in Cape Town, ‘tell me I haven’t died and woken up in the land yonder, the land of my ancestors.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘The food. White people’s food on my plate. No boiled mealie-meal kernels and boiled cabbage here, no bitter wild spinach here. Look at this! The white woman who dished it up for me called it beef stew.’

‘Come on, man, shut up and eat.’

‘No, man! I won’t shut up. The fact that I am eating so well is a sign of good things to come. Whoever thought the child of a humble African herbalist would be eating white man’s food, off a white man’s plate?’

Some of the men sitting not too far from them were probably thinking the same. They all came from poor backgrounds.

‘At this rate, I think, maybe by the time I get to the land across the ocean, my own face would have changed to white.’ The other men roared with laughter.

What made the food even more delectable, Tlali said, was that it had been dished up for them by white ladies. He wished his father could have been there to witness the spectacle. With a smile as bright as the morning sunshine, the lady who dished up the food had generously placed a huge spoonful of meat onto his plate. He had been about to move to the next lady, who was dishing up vegetables, when the first lady asked him, gesticulating with her hands, if he wanted more. Of course he wanted more. Who could refuse a white lady’s offering? So the white lady dished up more, and more, until his plate was as tall as the mountain overlooking their training grounds, the famous Table Mountain.

When the meal was over, an important-looking woman arrived. She was introduced to them as the wife of the Governor of the Cape. The men looked at each other, wondering what a “governor” was. Speaking through an interpreter, the wife of the governor wished them well on their journey. She solemnly promised that she would be keeping them in her prayers.

The recruits were then asked to stand next to the governor’s wife. A photograph was taken. Things happened too fast for Tlali to make sense of them immediately.

After dinner, as they were walking back to their sleeping quarters, Tlali was still in his element, telling stories and fantasising about life in Europe.

‘Now that I’ve eaten my first white man’s meal,’ Tlali said, ‘I think I am well on my way to getting myself a white bride.’

‘Why would you need a white bride?’ one man asked.

‘Man, we’re going to Europe! There are no black women over there. Besides, why would I want to go looking for a black woman in Europe when there are so many of them here at home? This war is freedom for us to explore, man.’

‘Freedom,’ one man assented.

Tlali continued, ‘I’m just picturing my white bride. Perhaps with hips just so, wide enough to carry our children. Imagine the children. Grand, with a rich honey complexion, soft curly hair.’ He saw Pitso’s hands clench into fists and immediately fell silent.

One man argued, ‘I know we’ve been told we can’t touch white women over there. But what if the women want us?’

‘Exactly,’ said another man.

‘I just hope,’ Pitso said, ‘that Tlali is not going to embarrass us over there in Europe.’

‘What do you mean, I’m going to embarrass you?’

‘Tell these men how you’ve never slept with a woman,’ Pitso said to his friend, hoping to shut him up.

The men laughed and slapped each other on the back as they parted ways, each man to his own bed.

‘Now, gentlemen, as you close your eyes to sleep, think of the white brides waiting for us overseas,’ Pitso said, laughing.

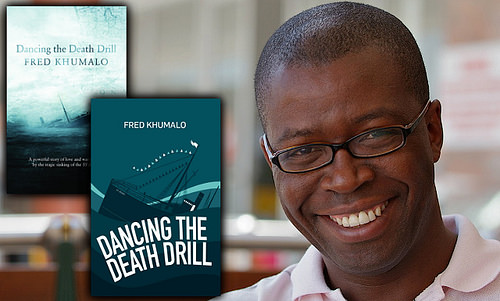

About the author

Fred Khumalo has been described as a ‘reluctant Zulu’, ‘clever black’ and an ‘equal opportunity offender’. He completed his MA in creative writing from Wits University with distinction and is the recipient of a Nieman Fellowship from Harvard University.

His writing has appeared in various publications, including the Sunday Times, the Toronto Star, New African magazine, the Sowetan and Isolezwe. In 2008, he hosted Encounters, a public-debate television programme, on SABC 2. His books include Bitches Brew, Seven Steps to Heaven and Touch My Blood.